Kenya

Freedom to be declined in the feminine

Words and Dialogue as a Response to the HIV Drama in Kenya

Exactly 43 years have passed since June 5, 1981, when the syndrome that would later be called AIDS was first reported. Two pages on Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the CDC in Atlanta: since that day, AIDS has killed over 36 million people and in Africa, where prevention is still lacking, this number increases year after year.

In a context like that of Kenya, where we were able to personally experience the reality that flows in the slum, we cannot ignore one of the fundamental factors that influence the spread of this disease: access to education. Without social equity there can be no quality education, and this is a risk that compromises the health of 7 out of 10 young people in Sub-Saharan Africa, because this is the percentage of women who do not know what HIV is.

They are not numbers, but stories. Like that of Rosemary, mother of three children, who experienced the stigma of the disease first-hand and was able to transform it into emancipation. Rosemary's desire for emancipation was not only a consequence of marginalization, but was born with her. She carries it with her, it is engraved in her eyes when she tells of having been a child who, with a ball of torn paper, loved to play soccer with her brothers, sang and danced without hesitation, studied with dedication but was prevented from accessing high school. Her family conditions - she says - did not allow her to live the life she would have wanted, hindered first of all by an alcoholic and violent father, directed early on towards work in the sugar cane fields and far from books. After the imposition of an arranged marriage she began to work as a washerwoman and, very soon, became pregnant with her first child, but she and her husband were not in a position to support the arrival of a child. The attention and care were not enough and Rosemary, two years later, lost that child due to severe malnutrition. A part of her died that day, but she still managed to react and, in the following years, after three more pregnancies, she discovered she had HIV. It was 2004, as reported by AICS, and in the shanty town of Korogocho, where Rosemary lived at the time, they even prevented her from using the public toilets. In 2004, the echoes of the Durban conference resounded, the first congress on AIDS in Africa which had as its theme precisely “Break the silence”, the urgent need to break the silence on equal access to care, better prevention, and government support for education.

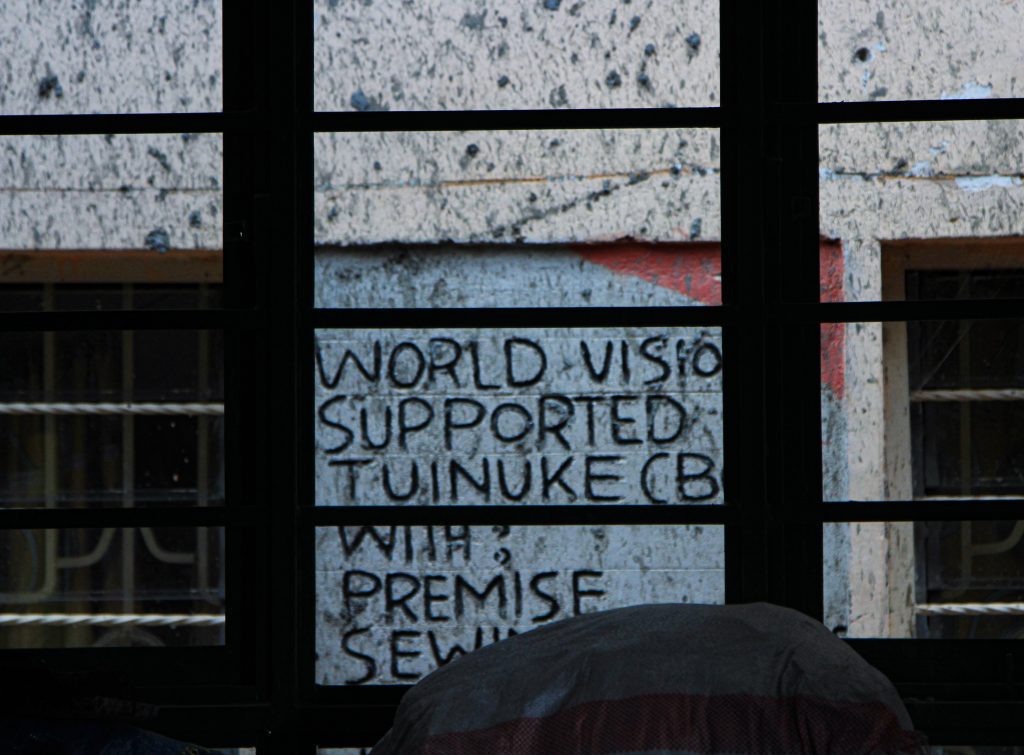

The turning point came in 2005, when together with four other HIV-positive women, Rosemary founded the association Tuinuke Na Tuendele Mbele. This association is a revolutionary reality, because it proposes to immediately address the social challenges that affect HIV-positive mothers, especially in settlements such as slum of Korogocho. The aim is to improve the standard of living of women through education and income-generating activities, with the mission of empowering and stimulating development by providing institutional support to local communities. Twenty years later, the socio-cultural context in which it has made its way Tuinuke Na Tuendele Mbele not much has changed. "There is more awareness," she says, "but the influence of the church elders is still strong, so freedom of choice is limited. Tuinuke was created to give HIV-positive women a place to get information, a voice, and a place to work with pleasure, fighting stigma and discrimination, but above all to be economically responsible in the family."

As explained by Jaids (Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV infection from mother to child, a broader integration of family planning, maternal and child health and reproductive health services is needed. The fight against poverty, access to education, support for personal planning and emancipation are fundamental elements.

I don't expect much from my hotel stays when I travel for business. It's enough that they are simple, clean, 24 hours a day, I've stopped hoping that breakfast includes my stupid routine yogurt. If I'm lucky I can book a hotel with a gym, especially after long flights with stopovers and intercontinental flights. I try to reset my heart rate with some healthy physical activity, in this way I think I can reduce the female imperfections of microcirculation and the effects of jet lag. Before booking the hotel in Jeddah I therefore contacted the reception to make sure I could access the gym. After my two previous stays in Riyadh, I knew I could stumble upon a hotel with a gym reserved for men and women in separate shifts, or in a "Fitness gym women only" in public spaces. The first time in the capital the receptionist had in fact prevented me from going for a run on the treadmill in the morning, even though the men's shift was completely empty. It seemed crazy to me, even though I had told myself to be good. But no, I went to the back courtyard of the hotel, in a neighborhood built on sand where there didn't seem to be a living soul, and ran, away from prying eyes, I knew I wasn't dressed according to the law, I was in Bermuda shorts and short sleeves. In the country, foreign women have been allowed to walk around without wearing the abaya, without covering the head, it is sufficient that they wear loose-fitting clothing that covers below the knee and below the elbow, without exaggerating with make-up. Most Saudi women, however, still wear the niqab, only a few show their wonderful Arabic features and olive skin in the sunlight, although sometimes it unsettles me to notice how many of them operate on their irises to show their blue eyes. In all Muslim countries, especially here, I regularly meet them bareheaded in the toilet, smiling and extremely supportive of each other, intent on combing their hair, making themselves beautiful, finally rinsing themselves after suffering the high temperatures under their black clothes. I have met some by chance in coffee shops or at work. They have also recently been allowed to go out alone in public places, as well as meet with people of the opposite sex without having to separate in rooms reserved for men and women. The first time I met a Saudi businesswoman was a few years ago at the Dubai fair, I could only see her eyes, and she was still so convincing, determined.

Our journey did not end in a tailor's shop, but the perception of gender inequality is not so different in other areas of Kenya. In Mombasa we met Celestar, a young and enterprising girl, who confirmed to us that the stigma on HIV, even today, keeps many people away from treatment centers: "There is no real national program, but there are women who personally take on the responsibility of providing information and prevention in our schools". Celestar perceives a strong split between formal law and cultural practices, which is especially noticeable in the world of work: she is a DJ, discrimination affects her firsthand. "Men do not admit that you have opinions, they often oppress free choice, they favor the careers of their sons and oppose female emancipation" explains Celestar, who adds that there is inequality, even today, in the school system.

There are, however, some exceptions, such as the matriarchal village of Umoja, an example of resilience and determination where a safe haven is offered to victims of violence and discrimination. From the interviews conducted during the trip to Kenya, a perception of tradition emerges as a reflection of male will, because they hold women back and suffocate their fundamental rights.

Stories like Rosemary's are revolutionary, but so are words. Folk poetry in East Africa has provided a means for communities to process the trauma of HIV/AIDS, offering firsthand accounts of its devastating consequences and contributing to the understanding and management of the disease. Art is a powerful tool for raising awareness, and poetry has been used as a means of communication and social negotiation, making the conversation about the disease more accessible and relevant to the local community. And words, dialogue, continue to be a tool for overcoming stigma, which is why exploratory travel is a fundamental means for building a network for exchanging knowledge, for creating a connection between women that goes beyond the borders of a single country, for reminding us that being Free to Travel brings with it the need to share this freedom, to share experiences and knowledge with a view to decolonizing the mind. The processes of change are being triggered, and they are not to be declined only in the feminine.

Nicole Pizzolato (@ni_edm) and Lara Berthod (@laraberthod) of the project Free to Travel (@liberediviaggiare) met and interviewed Rosemary during a trip to Kenya, creating together with the journalist Alessia Taglianetti (@alessia.taglianetti) the report that you can read on the NOSIGNAL platform by clicking on link

For information on volunteer experiences at the Carlotta Toniato tailoring shop (@lamad.0nna)