UZBEKISTAN

My journey through Uzbekistan, amidst the steppe, ancient traditions, and the timeless magic of the Silk Road.

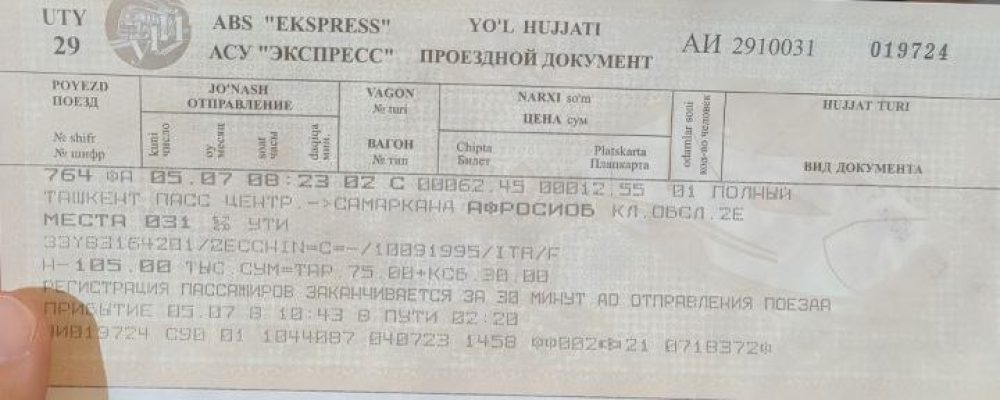

Tashkent station, 8.30 am

E’ un giorno così strano, questo. Sono in Uzbekistan per lavoro, pare che a breve salirò su un treno che mi porterà a conoscere un nostro cliente. Destinazione? Samarcanda. Sembra uno scherzo. Oggi scoprirò se questa città leggendaria esiste davvero.

Early in the morning, at the Tashkent station, the dry heat of the July steppe announces that it will be a hot day of travel. Who knows if I will encounter the Samarkand of myth, if I will find the languid, colorful and perfumed atmospheres imagined in orientalist autosuggestions. The passengers circulating in the hall munch on sunflower seeds, others take their places piling up luggage and saddlebags, baskets of fabulous Uzbek bread, cartons of pomegranate juice, toys, the iconic Muscovite chocolate bars of Alenka.

Once on the Afrosiyab train, the “tea lady” wakes me up to give me a drink and pass me a packed lunch offered by the railway company. After all, we are on the Silk Road, tea is ritual, rhythm, contemplation.

In Samarkand, a driver with an unpronounceable name awaits me, with elongated and friendly eyes and the usual raven fringe that is in fashion in these parts. Out of courtesy or custom, my local contact thought it necessary to have a driver escort me because I am a "single girl and not an Uzbek, our guest". However, I believe I can move independently, and I suggest to the driver that we meet again in the late afternoon for a slice of melon. Getting around Samarkand is simple, it is an orthogonal urban plan, with cemented parks, widespread cayhaneAlong the way, street vendors selling bread alternate with steaming samovars and the smell of doner, a brief summary of the country's souls: caravan, post-Russian, Turanian, Arab, timidly winking at the West.

Although the city is now opening up to international tourism, Samarkand and its inhabitants still seem very traditional. Here and there there are giant statues that celebrate in a very Asian way the cult of personality of Tamerlane and further on the giant statue dedicated to Islom Karimov, born and raised in Samarkand, former satrap regent of the USSR Republic, who passed away in 2016. He left a controversial legacy, between resentment and nostalgia. Since Karimov's death, the country has become the most populous of the "stans", one of the fastest growing in the world, very rich in mineral, energy and agri-food resources, finally open to foreign investment. Due to its strategic position, even though it falls into the category of landlocked countries, is the object of contention between the great powers competing in the renewed climate of the Great Game: Russia, Türkiye, the EU, the United States, China.

Geopolitics aside, the true symbol of Samarkand's history is the majestic Registan Palace (Farsi for "place of sand"), dating back to the 15th century. The square in front of it is crowded with young brides, called kelin, they are all so serious. I ask someone: “why?” They kindly explain to me that it is local custom for the bride not to smile and to keep her head bowed so as not to give away whether it is a love marriage or an arranged marriage. I want to know more. I discover that in 2022 a survey conducted by the Uzbek Institute for Family and Women Research revealed that 39.9% of the couples interviewed got married through sovchilik, a traditional matchmaking practice initiated by parents and other older relatives, while 33.9% married based on mutual interest. In 2019, the Family Code officially eradicated marriage under the age of 18. However, families continue to arrange marriages through informal religious ceremonies, i nikah, without any local registration. The country’s opening to globalization has inevitably affected the functioning of centuries-old family dynamics. The popularity of social media has made it urgent to settle daughters, who traditionally must marry virgins. The danger of daughters being exposed to the web increases the possibility of unspeakable dishonor for families, especially in rural areas. However, the rift between modernity and tradition seems to be starting to heal. On April 30, 2023, Uzbeks voted in a referendum in favor of reforming the Constitution, which establishes a legal, social and secular state, and includes a package of amendments to the penal code that criminalize domestic violence and guarantee new protections for women and children. Uzbekistan is currently ranked 94th in the Women peace and security index, which evaluates 177 countries in terms of inclusion, justice and security for women.

The other day in Tashkent, the capital of the future, B was telling me about his wedding before hosting our staff in one of the trendy clubs around Tashkent City Park, a futuristic sight. He is married for the second time, and seems happy about it. The first time he had to get into debt up to his neck to be able to afford a wife, he had bought a very expensive piece of jewelry, nothing compared to the luxury goods that many of his peers have to invest in to prove they can provide for their future bride. This business has practically ruined his life, now he has a little girl, and he is forced to pay the installments of the pledge from the previous marriage for life. “The fact is that society is now changing in Uzbekistan too,” he says. “Although people still get married very young, more and more women are starting to work, jeopardizing the family mechanisms I am telling you about. Everything that happened in the past seems to be creaking now. Sometimes it happens that we young people get into debt and divorce soon after, especially in the city, triggering a distressing vicious circle”. This is the millennial generation in Uzbekistan, caught between Islamic traditionalism and post-Soviet atheism. Even as they face globalization, Uzbeks of my generation are trying to recover their identity after years of communism. Many of them are keen to point out that those seventy years of regime have devoured local culture and say they are tired of foreign interference, although the feverish anxiety to adapt to the Western model is tangible. And… when the so-called “free world” meets the cultural marker, anguish takes over.

While Uzbekistan in 2024 is throbbing with change and projecting itself into the future, Samarkand is real, right in front of me, and its inhabitants sit comfortably in the inner courtyard of the palace. The men wear colorful Uzbek crocheted hats, the women wrap their hair in soft fabrics. In the courtyard of the Registan, some sell carpets and fabrics in the former study rooms of the madrasas, others squat barefoot on large wooden benches to rest; some women sit on the floor with their daughters to display scarves, others drink tea on small terraces, or carve cute, characteristic gnomes out of wood. Everyone goes about their business, placidly, when I meet their faces they seem so ataractic, at peace, it seems like they are smiling, even if in reality they don't, it's as if there were an insurmountable barrier between me and them even though it is so easy to receive their serenity. This is the adorable enigma of the Asian spirit. A young man then contradicts me at the Bibi-Khanym mosque, telling me that even the great leaders of Central Asia have actually come to terms with the most banal human feelings. It seems that it was the beautiful Chinese wife of Tamerlane who ordered the construction of this architectural jewel during her husband's absence. Accidentally, the architect in charge fell in love with her. Tamerlane soon had him executed upon his return, imposing that all women wear the veil, so that the men would not fall into temptation.

I reflect on how many cultural similarities have survived to this day, as I visit the most impressive and unique monument in Samarkand, the Shah-i-Zinda, “the tomb of the living kings”, a necropolis of incredible craftsmanship, a marvel of tiles, terracotta and turquoise majolica in which one of Mohammed’s cousins also seems to be buried. It is an unforgettable, silent, spiritual place, where you can reconnect with a more ascetic dimension, at the end of which you reach the cemetery of Samarkand, a fascinating park in which to walk and discover on the tombstones the curious snapshots of the last century, of the Uzbeks who were. Before returning to the city I enter the old and silent core of Samarkand, a tangle of unmapped, identical, crooked, closed streets, I confess to feeling fear. I stumble upon the city’s Sephardic and Ashkenazi synagogues by chance, when an elderly gentleman invites me to visit his courtyard, where a series of delightful knick-knacks are piled up (glasses, plates, busts of Lenin and other Soviet leaders, carpets). Then I meet a sweet lady who is hanging out the laundry, in Russian she asks me where I am from, smiling adorably when I tell her I am Italian, without fear of letting me glimpse her complicated teeth.

I'm late for my morning appointment with the driver, for that promised feast of sweet melon on the way back to the station.

Before saying goodbye, he wants to show me the place that makes the inhabitants of Samarkand most proud, the tomb of Tamerlane. It's worth it. When I cross the monumental portal I immerse myself in the absolute and obsequious silence of the mausoleum, whose interiors are embellished with deep niches decorated with muqarnas, plasters and high reliefs covered in gold. Gold is prevalent, never exaggerated, it envelops me with a strong sense of royalty and solemn hieraticism. Anyone who tries to violate it could be punished: on the tomb of Tamerlane I read an inscription: Whoever violates my peace in this life or the next will be subject to inevitable punishment and misery. Wow, I think Tamerlane has me under his spell.

I have to hurry, I'll be late for the last train to Tashkent.

Taking the train means giving yourself the time you need, watching the landscapes pass by and the stations come to life, observing the people you are travelling with and yourself, swaying on the suspensions. In front of me is a French couple, father and son, they are commenting on the extraordinary day they have experienced in Samarkand. In the rest of the carriage only Uzbeks, who also have a carton of tea to take away, as if the “tea lady’s” tea wasn’t enough. The daylight is fading and there is no better moment to abandon yourself to the steppe, yellow, ochre, faint, uniform… so flat as to arouse the most tangled thoughts, almost as if that boundless space were waiting to be filled by the contents and thoughts of a young intruder who happened to be in the eternal city of Samarkand on any given day, existing, stopping, disappearing, without forming part.

Article and photos by Claudia Zecchin. You can also find the article on the blog www.cinnamomo.com